I Assembled a Tiny Ramen Stall and Accidentally Found Zen in Software

The value of slowing down, paying attention, and caring about the craft.

I’m enjoying the first months of fatherhood and, surprising as it sounds, it feels like I can hit the pause button for once.

As one does, I turned some of those pauses into Existential Decluttering™ moments (or tidying up à la Marie Kondo if you will).

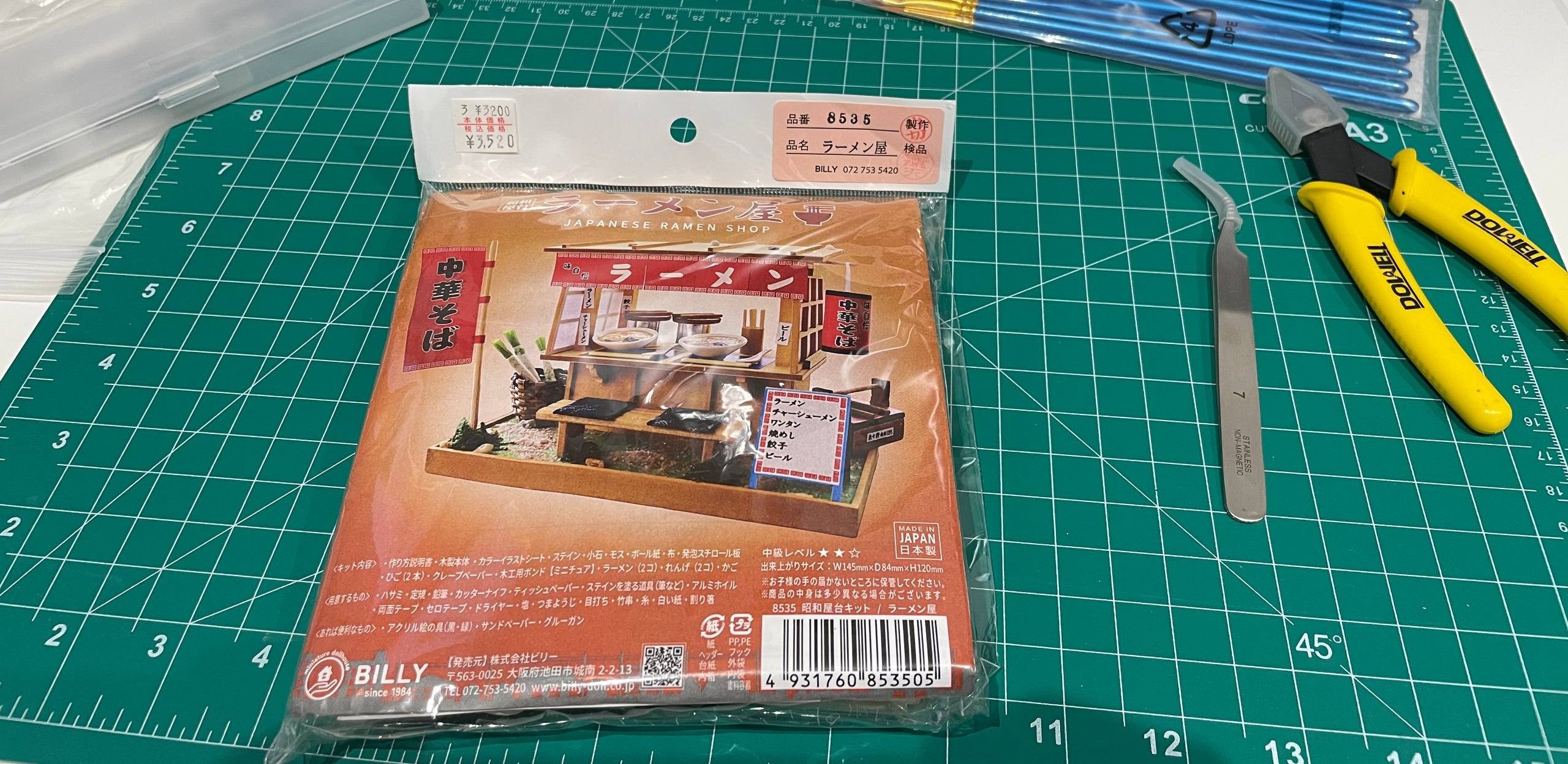

And amidst the tidying, I came across this DIY miniature ramen stall kit that I bought last year in Japan. One of those with super tiny pieces and unclear Japanese instructions.

I’m not making this up!

I’m not making this up!

While building it, I stumbled upon a few thoughts that, of course, only the Japanese1 would already have a name for.

Yutori (ゆとり)2 or Slowing Down Against Productivity

Literally “spaciousness”, “leeway”, or “room”, the Japanese use this concept to express the philosophy of slowing down, avoiding constant busyness, and prioritizing mental and physical well-being over relentless productivity.3

When you build software for a living, your days are measured in velocity. Quarter objectives, sprints… call them whatever you want. They all want one thing: to be as productive as possible, to finish as soon as possible.

But you cannot rush assembling a miniature ramen stall kit, at least not more than your hand motor skills allow you to. Everything depends on how steady your hands are. There’s glue that needs to dry, paint that needs to settle, and did I mention instructions in Japanese? (which is not just about the language)

Glue doing it’s thing

Glue doing it’s thing

Somewhere between the drying, the waiting, and scanning instructions with Google Translate, I remembered what it feels like to actually enjoy the craft. Not optimise it, not monetise it but just to enjoy it.

Nowadays, with the rise of AI tools, we don’t just rush the craft, sometimes we skip it entirely, outsourcing the joy of making to a machine. Let that sink in.

There’s a kind of quiet joy in slowness that we are forgetting more and more about in tech. When you stop measuring output, you start noticing texture. And somehow, counterintuitively, it makes you feel more productive and fulfilled.

Or maybe yutori isn’t about moving slowly at all, and it’s about having room inside yourself, even when things move fast.

Wabi-sabi (侘寂) or Finding Beauty in Imperfection

Wabi-sabi is a Japanese aesthetic and philosophy that finds beauty in imperfections, impermanence, and incompleteness.4

You can’t cmd+z in life nor can you while assembling these kits. My hands can’t be as precise as my CSS when striving for pixel perfection.

But that’s a feature, not a bug (yes, in life too). Seeing the miniature stall finished, with all its imperfections, it looked different than the one in the packaging. I put the hanging lantern facing the wrong way, the bench cushions are way too big, the chopstick handler is all cracked because I used too much glue. It’s imperfectly perfect in its own way, unique in the world. It tells a story no other miniature ramen stall can tell.

These potato shaped ramen pot lids were meant to be circular

These potato shaped ramen pot lids were meant to be circular

It’s honest. Authentic.

Have you noticed how everyone sounds exactly the same lately online? Everybody is using em dashes and sounding so… flawlessly boring. Hey, I use ChatGPT quite a lot too, and I’ve also been guilty to let it write more than I should. But lately I’m using it more… responsively (if that’s the word). To fact-check. To refine. But not to erase my voice.

The way I see it, in the AI era, our flaws will matter more than ever. They’ll keep us honest, authentic, human, in a world driven by LLMs.

Shokunin (職人) or Putting Care in the Craft

People often translate shokunin as “craftsman,” but it isn’t just about skill or a trade. It’s devotion, a mindset. Showing up with care, humility, and pride because doing something well is a way of honoring others, not just yourself.5

I’m not a woodworker in a Kyoto workshop. I just build web applications (and occasionally tiny ramen stalls).

I know, it’s just a miniature ramen stall.

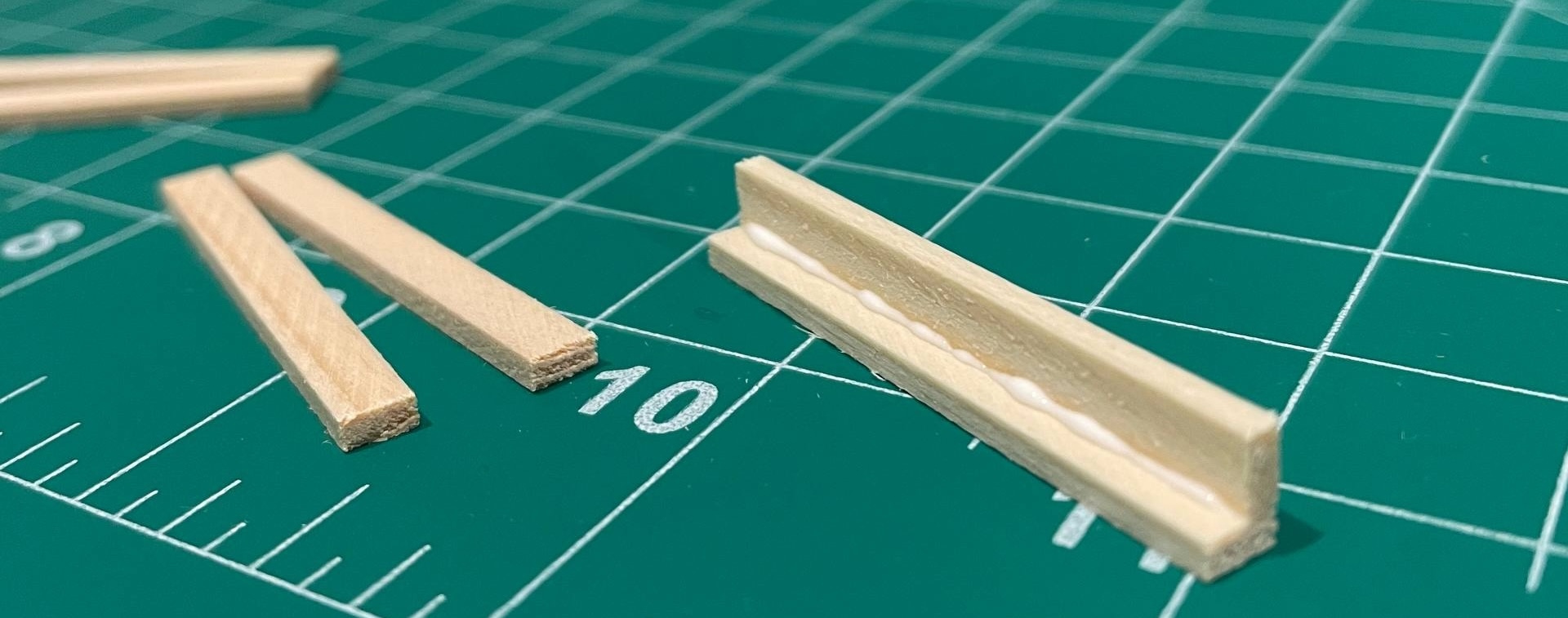

But somewhere between the glue drying and me holding my breath to place a 3mm chopped piece of wood to assemble one of the windows, I started thinking about craft, and how I want to write software the same way.

Assembling the windows

Assembling the windows

Anyone can generate code that works nowadays. But not everyone can care about the details, the intent, the taste, or the responsibility of making something that reflects judgment and pride.

And I want to be proud of what I ship.

AI is just a tool. Craftsmen moved from manual saws to power tools, and now co-write code with models. That didn’t make carpenters care less about how they assemble their work, and we don’t stop caring about the code we ship.

Shokunin isn’t about typing every line yourself. It’s about how you show up to the work. The part you refuse to outsource because it matters to you.

And the discipline to keep improving even when no one sees it, or when the AI creates the illusion that you don’t need to.

AI is an accelerator, but it won’t replace the spirit.

Final Words

I’m far from becoming the next programmer-zen master (so far, I just have two bonsai and a tiny hand-assembled mini ramen stall in my living room) but I hope these reflections sparked something in you.

I know how the Real World™ works, and that things evolve, but I think keeping a bit of Yutori, Wabi-sabi, and Shokunin in how we build things would do us all a favor.

As the greatest sensei once said:

“First learn balance. Balance good, karate good. Everything good.” — Mr. Miyagi

We don’t keep it the miniature here, just wanted to show off one of the bonsai

We don’t keep it the miniature here, just wanted to show off one of the bonsai

-

If any Japanese readers come across this and notice imperfect interpretations, thank you for your patience and understanding. I approach these ideas with profound respect and curiosity. ↩

-

Yutori is written only in hiragana, there’s no kanji form for it, which is fairly unusual for a conceptual word in Japanese. ↩

-

The term yutori originally became widespread through the “Yutori education reforms” (ゆとり教育) in Japan around the early 2000s, meant to reduce academic pressure and encourage creativity. Over time, yutori evolved to mean a mindset of having margin — emotionally, temporally, mentally. Its modern use sometimes has a faintly negative tone (“the yutori generation” being seen as softer or slower) ↩

-

If you want to dig deeper in the concept, I highly recommend Wabi Sabi: The Wisdom in Imperfection by Nobuo Suzuki, very light but powerful read. It’s already in my reading list, where you can find other recommendations. ↩

-

This barely scratches the surface, it’s my partial interpretation, shaped to fit the idea I’m sharing. For an explanation from someone who actually knows what they’re talking about, read more. ↩